The North

Carolina Letter Carrier

For

Al Friedman, the NALC Food Drive is in the

Bag

Al Friedman’s success as a NALC food drive coordinator began where most success stories begin. It began with a passion.

“I always had a passion to help the elderly in Florida,” says the current Florida State Association of Letter Carriers’ president and Region 9 Food Drive coordinator. “There’s a high percentage in Florida. I was coordinating Carrier Alert at the time, checking on the elderly.”

Friedman’s branch, Clearwater Branch 2008, has been involved in the nation’s largest single-day food drive for the past 21 years. How successful has his branch been? Last year Clearwater alone collected 1,275,289 pounds of food.

And much of that success has to do with bags. The kind of bags you find in your local grocery store.

About 16 years ago Clearwater’s food coordinators wondered if they might be able to collect more food if they delivered bags with the postcards advertising the NALC Food Drive. They decided to experiment. The first year they delivered 300,000 bags with the postcards attached.

The result of their experiment was quite impressive. They wound up collecting 500,000 pounds of food.

“Right then,” says Friedman, “we knew this was successful.”

Since Clearwater was the only branch using the bags at the time, they presented the idea of using bags to their state association. The membership thought it was a great idea and one worth pursuing.

But what food chain was there that could provide them with enough bags to cover the entire state of Florida?

Ultimately, the search led them to Publix Super Markets. Founded in Winter Haven, Florida in 1930 and with its corporate headquarters located in Lakeland, Florida, Publix is the largest employee-owned grocery chain in the United States with its largest concentration of stores in Florida.

Subsequently, a meeting was set up with representatives at Publix. At the meeting Friedman asked the company for 2.5 million bags.

“If we provide you with 2.5 million bags, how much food would that generate?” asked the Publix people.

“If we get two, eight ounce cans per bag,” Friedman told them, “we can get, at minimum, 2.5 million pounds of food.”

Publix: “How many deliveries are there in the state?”

“It’s just shy of 8 million households,” said Friedman. “That’s residential, not including businesses.”

Next question: “If we supply you with 8 million food bags, would you be able to get 8 million pounds of food?”

At this point in the discussion Friedman thinks, 'Am I now saying something I can’t deliver?’

“But I figured,” says Friedman, “Let’s go for it.”

So, they went for it. And the gamble paid off. The first year with Publix, Florida’s letter carriers collected 8,400,000 pounds of food. And that amount has been growing every year since.

In addition to donating millions of bags to the letter carriers’ food drive each year, Publix also places marquees advertising the food drive in every one of its stores.

“I was amazed,” says Friedman, “that this company is so into helping us feed the hungry.”

Each year, when the food drive results are published in the July Postal Record, Friedman sends Publix a copy.

Then, he takes it one step further.

“I ask the food banks to write a letter to Publix thanking them for joining the letter carriers in helping to stamp out hunger. I tell the food banks that it’s because of these bags that we have nearly doubled our food collection.”

Three years ago when Publix opened stores in Charlotte, NC they contacted him asking how they could get the bags started there.

“I said, ‘That would be great, but can you do the entire state?’”

Their response: “Just tell us how many bags you need.”

Friedman notes that when the bags come into the office they need to be broken down and distributed to the carriers’ cases. Additionally, he says there are significant ways to make delivering the bags easier on the carriers.

“The bags, which come 2,000 to a box, are already perforated to tear away. There’s a little loop at the top of these bags that you can put right over the light switch in the LLV so they hang perfectly flat against the dashboard. As you pull up to the mailbox, you rip off the bag and put it right in. It’s less cumbersome and very easy to do.”

As for delivering on walking routes or park and loop, Friedman says he knows of one enterprising carrier who uses a hiking belt with little hooks on it. He puts his bags over the hooks, then when he delivers the mail he just grabs a bag and pulls it off.”

The relationship between Region 9’s letter carriers and Publix has been a win-win for everyone involved.

“I had an email come to me from Publix when we first started using the bags in Charleston, SC. They tell me that the headlines in the paper read that the city’s letter carriers and Publix are stamping out hunger by collecting food.

“They tell me, ‘You just can’t buy that kind of advertising.’”

Al Friedman (far left), former NBA Matty Rose, former governor Charlie Crist, NBA Kenny Gibbs and some of Florida’s letter carriers promoting the NALC Food Drive.

Anna’s Story: Sometimes the Impossible is Possible

This is a kind of Christmas story. It doesn’t take place at Christmas, but it has the feel of Christmas. After all, the original Christmas story that played out in history 2000 years ago was a miracle. Christmas is a good time of the year for sharing stories about the miraculous. This is such a story. It’s Anna’s story.

One of the first things you notice when meeting retired Wilmington letter carrier Mike Alabaster is his smile. Mike doesn’t just grin, he SMILES. Literally, he smiles from ear to ear.

But on September 11, 2006, Mike didn’t have a lot to smile about. Now you would think it would have been an occasion that would have made him smile. After all, he had just become a brand new grandpa. His granddaughter, Anna Marie Formy-Duval had just been born at New Hanover Regional Medical Center.

It should have been an event punctuated with smiles and laughter and tears of joy.

What joy was to be had that day had been overshadowed by deep concern for this tiny new born baby.

You see, Anna wasn’t a typical tiny newborn baby. She was a micro-preemie. She had been born three months premature. At 10 1/2 inches long and weighing in at one pound, two ounces, Anna’s parents, Charles and Karen Formy-Duval, were told by the doctors that if—and it was a mighty big if—IF she survived birth, she had less than one percent chance of survival. And IF she survived, she would have no quality of life. Let that sink in, parents and grandparents. That tiny baby, even if she lives, will have no quality of life. None. Think about it.

So, with that kind of prognosis at the

very beginning of Anna’s life, you can understand why there wasn’t a great deal of joy to be had that day.

But they did have something that maybe the doctors didn’t take into consideration. They had faith. And they had hope.

Recalls Anna’s mom, Karen, “We understood that she might not survive, but we wanted to give her the chance to show us what she wanted.”

And what exactly did Anna want?

Anna wanted to live. And she was willing to fight for it.

And so it was with the help of doctors and nurses and her parents and grandparents and friends and neighbors praying, Anna lived!

But living was just the beginning. That was just one hurdle. There would be many other hurdles to follow. It was obvious that Anna’s race wouldn’t be a sprint, it would be a long-distance run; it would be a race of endurance and will-power.

Anna would spend the next 15 months of her life in hospitals, with each day a question of whether or not she would survive. From New Hanover Medical Center she and her parents would travel to UNC at Chapel Hill. Then on to Duke. And then Pitt County Memorial Hospital.

For 15 long months it would be touch-and-go for Anna and her loved ones.

Says Karen of that time: “During those 15 months we went through every emotion imaginable and our faith in God was truly tested.”

Karen recalls one particularly rough day at Duke when the doctors were asking she and her husband to make some very hard decisions concerning their baby, the kinds of decisions no parent should have to make.

“My husband and I went to the chapel and some staff members from another area of the hospital came in for their own personal reasons and before they left they said, ‘We don’t know what y’all are going through, but it seems pretty heavy.’ They asked if we would join hands and let them pray for us. It was very touching that those strangers cared enough to do what they could to help us see through the dark cloud that was hovering over us.”

Karen admits that not all the medical personnel they met along the way were as positive about Anna’s future as they were.

“We dealt with doctors who were negative and didn’t want to give Anna a chance because the odds were against her.”

Try to imagine this, if you can. Your tiny baby daughter who—so far during her young life has had to fight for every breath she takes—is being evaluated for an important procedure. You, as a parent, are struggling daily to be strong for your baby, struggling to maintain the hope that your precious child will survive and one day will be able to finally go home with you. And a doctor, within your hearing, says this about your child’s procedure: “It would be a waste of their time and ours.”

Fortunately, for every insensitive doctor they met along the way, there were plenty of good ones too.

Slowly but surely Anna was making small improvements with each passing day. She grew stronger and hope grew stronger with her.

Anna began to make her biggest improvements when she was transferred from Duke to Pitt County Memorial Hospital. There was a pediatric pulmonologist there, Dr. Gerald Strope, who had spent his entire career treating children with severe and chronic lung issues.

“This doctor,” says Karen, “put all of his time and energy into helping Anna. You should see the care and compassion that he had for the children that were his patients. We cannot thank him enough for all that he has done for Anna and our family.”

Then a few weeks before Christmas 2007, Anna went home for the first time. And a lot of medical equipment went with her including a tracheostomy tube, a feeding tube, a ventilator, an apnea monitor, oxygen tanks and a pulse-ox machine.

Although Anna had been steadily improving prior to her going home, she began to do really, really well once she got home.

In 2009 Anna was finally able to breathe without the aid of a ventilator. That same year her tracheostomy tube was removed.

In 2010, she no longer needed to be on oxygen or the apnea monitor.

One by one Anna had successfully sailed over a number of hurdles that life had placed in her path, hurdles that some had predicted she would not be able to overcome. But she did.

Along the way there have been wins and there have been some losses. As the result of her having to use such high amounts of oxygen for such an extended period of time, Anna lost vision in her left eye.

“At the time,” says Anna’s mom, “that was devastating news. But in reality, that was minor in comparison to the other issues that she could have had.”

Those other issues could have included stomach/digestive problems, bleeding on the brain, seizures, and other neurological problems.

“It is absolutely amazing to me,” says Karen, “that Anna did not have any of the other issues that a lot of preemies, especially micro-preemies, have.”

As for those doctors who had predicted a zero quality of life for Anna? They were wrong. As a matter of fact, Anna’s quality of life is quite good. And it continues to improve with each passing day.

“Depending on your definition of quality of life, twenty-three weekers can still have a happy and fulfilling life,” says Karen. “Anna wakes up every day happy, energetic and enjoys every day to the fullest.”

Says her proud grandpa, Mike Alabaster, “Anna still has trouble communicating but she has come a long way in the last couple of years. She will talk (eventually), it’s just that she’s on Anna’s time. When she gets ready to do it, she’ll do it. We believe she will one day be able to do anything she wants. She’s going to be great at whatever she does, it’s just a matter of time.”

Mike retired from the Postal Service in 2009 after delivering Wilmington’s mail for 35 years. This has given him the freedom to look after Anna while her parents are working. He takes her to school in the mornings, picks her up in the afternoons. He and the family are quite pleased with the special needs teachers at the New Hanover County Schools.

And, like typical grandfathers, he readily admits that she has him wrapped around her little finger. This admission is accompanied by his neon smile.

“Even with all the stress, anger, and heartache that we have faced,” says Karen, “we would do it all over again. We learned to listen to our hearts, and know the true meaning of having your trust and faith in God.”

As for the numerous doctors she and her family have met along the way, Karen says that despite some of the strong disagreements they had with some of them, they still have a strong respect for them and what they do every day.

“Anna would not be here today if it wasn’t for the help of every doctor and their medical teams, and for that we are truly grateful.”

She adds: “We cherish every day that we have with Anna and our families. Anna has taught us so much, but the biggest thing that she has taught us is that sometimes the impossible is possible.”

Gary Cappy: A Lifetime Dedicated to Social Justice

Up until a few years ago the NC State Association of Letter Carriers published a monthly publication, The North Carolina Letter Carrier, that was solely supported by advertising and the printing of what was then a paper, was done by a printing company in Georgia. Due to our long-time publisher having financial problems, the State Association’s membership voted to cut ties with them and begin publishing The North Carolina Letter Carrier in a quarterly rather than a monthly format.

That shift required some major changes to the publication you and your fellow retired and active letter carriers have been receiving for the last few years. One of those major changes required us to find a union printer who was closer to home. Our search led us to a small union printer, Grass Roots Press, located on Peace Street in Raleigh. It was owned and operated by the husband-wife team of Gary and Miriam Cappy.

Prior to submitting our first publication to them, I visited the Cappys at their business one afternoon and Gary sat down with me and patiently showed me what I would need to do in order to make our publication one that Grass Roots and the state’s letter carriers could be proud of.

The letter carriers of North Carolina could not have found a better man to print The North Carolina Letter Carrier than Gary Cappy. When we think of a publication like this one, we think of its various contributors who write for it, and the editor who edits and organizes it. But we often overlook the people who print it! The North Carolina Letter Carrier could not be the publication it is today without the dedication of Gary Cappy and his wife Miriam.

And so it was with heavy hearts that we received the news that Gary had passed away back in August.

In an effort to honor his memory, we are reprinting below the eulogy that was posted on the Grass Roots Press Facebook page:

“It is a sad time as we mourn the untimely loss of our beloved Gary from complications of a recent diagnosis of Amyloidosis. His lifetime of dedication to social justice has left an indelible mark on the communities he touched, but he will be deeply missed by his friends and family and especially his wife of 34 years, Miriam.

“Gary Edward Cappy passed away at Raleigh’s Rex Hospital after a courageous battle with amyloidosis. He was born in New Eagle, PA and attended West Virginia University. After college, Gary devoted his life to social justice activities. He worked with the UFW on the grape boycott in Pittsburgh and later moved to Bakersfield to work with Cesar Chavez unionizing farm workers. It was in California where he learned how to print.

“Moving to NYC, he met Miriam Melendez at NYPIRG while working there in the print shop. Gary and Miriam were married in June 1981 and established Grass Roots Press in NYC before moving to Raleigh in 1988. He was a proud union member of CWA Local 3611. He was an avid fighter for the underdog and attended as many Moral Monday rallies as he could.

“Gary is survived by his wife, Miriam, his mother-in-law Lucy, his aunt Frances Klasan of PA, uncle Robert Cowell of CA, cousin Jennifer Dowler of Greensboro, NC, and countless cousins and friends.

“A celebration of Gary’s life took place on Saturday, Sept. 12th at Edenton Street United Methodist Church in Raleigh.”

We are indeed thankful that Miriam, with the help of friends, will continue the work that she and Gary began together back in 1981.

National Business Agent Kenny Gibbs,

Jr.: Growing Carriers

for the Future

Ask a kid what he wants to be when he grows up and you’ll get answers like astronaut, fireman, policeman and scientist. Generally speaking, you won’t hear letter carrier.

But that wasn’t the case with the young Kenneth Gibbs, Jr. of Brunswick, Georgia.

“I knew I wanted to be a letter carrier,” says Region 9’s first African-American National Business Agent. “In my hometown letter carriers were seen as very important figures. It was an important job, a good job, and letter carrier was the most respected job in town.”

Who knows, letter carrier could have been imprinted on his DNA. You see his dad, Kenneth Gibbs, Sr. was a letter carrier in Brunswick. And he was also an active member in Branch 313, serving for a while as its secretary-treasurer. Undoubtedly his father had a great influence in his son wanting to follow in his footsteps.

And so it was that in 1980, not long after graduating from Brunswick Junior College with an Associate of Science degree, he was hired by the Brunswick post office as a city letter carrier. It would be a position he would hold for the next 23 years.

The first thing he did upon being hired was join the union. Unlike a lot of young people today, he knew how important unions were for middle class working people like his dad and himself. Although his father was active in the local branch, Gibbs acquired most of his knowledge about unions from a research paper he had written for a high school assignment.

And this knowledge led him to pursue even more knowledge. “I began reading everything I could get my hands on,” recalls Gibbs. “I wanted to know my rights and I couldn’t get that unless I read it myself. I went to all the union meetings and I became active in the state as well. That’s where the training was.”

Some things in life you learn from your parents, from school, and from books. Other things you have to learn from experience. One such experience for the young Gibbs came early in 1981 not long after he became a letter carrier and union activist.

The time had come for the National Agreement to be renegotiated between the NALC, the APWU and the Postal Service. As has often been the case over the years, there was tension between the parties even before they sat down at the negotiating table. Postal management was proposing freezing wages and capping the COLA. Not surprisingly, the NALC and the APWU were opposed to that. There was picketing around the country and a nationwide rally conducted in Washington, DC in the spring of that year.

At the rally, NALC and APWU leadership notified their members that all options were on the table, including the possibility of a strike if USPS pursued their reported agenda.

Recalls Gibbs: “I was a PTF at the time. We had a meeting and talked about going on strike. I met with all these men who had been my dad’s friends and they were talking about walking out on their jobs. It was overwhelming to me as I realized this was a big deal.”

Fortunately, a strike wasn’t necessary. On July 21, 1981, the two unions and the Postal Service reached a satisfactory agreement in which an uncapped COLA remained in place, wages were increased, and mandatory route inspections were eliminated.

For the next decade, Gibbs would serve Branch 313 by volunteering for anything and everything that became available including sergeant-at-arms, trustee, food drive and MDA coordinator, joint route inspection co-leader, health benefits representative and vice president. So when the current president Edward Lowe retired, he felt prepared to serve as the branch’s president.

While serving in those positions, carrying mail, and raising a family, he also was serving on the Georgia executive board, first as treasurer, then vice president, and then president.

In 2003, after serving just nine months as the Georgia State Association’s president, he was asked by then NBA Matty Rose and NALC president William Young to serve as one of three Regional Administrative Assistants for Region 9.

The transition proved to be a challenge in more ways than one. For example, representing four states was different from just representing one state or one branch.

“There are many different things done different ways and you have to be able to do them all,” says Gibbs of the transition. “You have to apply the contract the same regardless of where they’re from. I couldn’t say, ‘This is the way we do it in Brunswick,’ or ‘This is the way we do it in Georgia.’ That was a big transition.”

Another challenge was just having to make the decision about whether or not to move himself and his family to Ft. Lauderdale, Florida.

“That was the biggest debate,” says Gibbs. “It was a nice community to raise a family. I did make that choice and I don’t regret it.”

He served as RAA from 2003 until 2014. Then, at the NALC’s 69th Biennial Convention in Philadelphia, he ran unopposed and was elected Region 9’s National Business Agent, succeeding the region’s first female NBA, Judy Willoughby. Willoughby went on to be elected as the NALC’s Assistant Secretary-Treasurer.

He says that under his leadership at the NBA for Florida, Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina, letter carriers should expect changes in the way training is presented. “But they will be changes for the better,”

Looking at the diversity of people in the union he says, “We have a lot of people and a lot of talent. A good example is Natalie Davis out of Durham. She’s a very quiet lady. Most times you don’t even notice her. She got up at a recent panel of expert’s presentation and spoke very articulately. Most people didn’t know she could speak like that. But now they know because she had the opportunity to shine.”

One of his passions is developing new leadership talent and helping them find their full potential.

“I’ll be trying a lot of different things that involve people who haven’t had the opportunity to get up in front of the state and teach. That’s how I came up, teaching as a state officer.”

Another challenge will be to get more CCAs involved and engaged in the union. Because they are younger and because the union movement’s influence as diminished in recent years, they are unaware of how important the union is.

“They come into a demanding job like the Postal Service,” he says, “and they don’t have that foundation of unionism. We’ve got to teach them that, teach them why we’re so strong.”

Married to his high school sweetheart, Linda, they have three grown daughters—Angel, Angelina, and Angela, and five grandchildren. Will one of those kids follow in grandpa’s footsteps?

Region 9's National

Business Kenneth "Kenny" Gibbs, Jr.

High Point Letter Carrier Delivers Aid to

Elderly Customer

Because letter carriers spend so much of their time on the street, it’s just a matter of time before they find themselves confronted with an emergency situation in the community.

Case in point, High Point letter carrier Stephen Hancock. Back in February while delivering mail on his swing, Hancock saw an elderly woman out in her yard, walking her dog. Pulling excitedly on its leash, the dog caused the woman to lose her balance and fall.

Noticing that the woman was struggling to get up, Hancock stopped his vehicle and asked the woman if she needed help. Although she assured him that she would be alright, Hancock waited to see if she would be able to stand.

“I noticed she wasn’t able to get up,” says Hancock, “so I went to assist her.”

In helping her to her feet, the carrier noticed that she was unable to put weight on one of her legs, so he carried her into her house.

Hancock learned a short time later that the woman had suffered a broken hip and a broken leg and was expected to fully recover from her accident.

This accident occurred in the winter and raises some relevant questions: How long would this elderly woman have laid there in the yard if Hancock had not been passing by when he did and seen her fall? What if he had been so focused on delivering the mail that he hadn’t noticed the woman’s plight? Or what if he had seen her fall, but because he was in a hurry, just assumed she was okay and driven past? Under similar circumstances, what would you have done?

Asked if he had ever been involved in a situation like this before Hancock says no, adding, “It was kind of scary and rewarding at the same time.”

***********************************************

"Six days a week, in every city and

town across America, proud union letter carriers travel the

streets and byways, serving every home and business along their

routes. Because these brothers and sisters are everywhere, every

day, they represent the front line of safety for many in our

communities, not only the elderly or the young, but Americans of

every age and in every station of life.

These good men and women believe that

serving America means more than delivering the mail. For them, a

vital part of "universal service" is a sense of universal

caring.

There are tens of thousands of courageous letter carriers all across America whose daily deeds of bravery and simple compassion make us all proud." --- National Association of Letter Carriers

Retiring state treasurer,

Danny Straub

The

End of An Era

For most of us the idea of spending a good portion of our lives keeping track of someone else’s income and expenditures, wouldn’t have very much appeal. Danny Straub, on the other hand, apparently enjoys it. After all, he’s done it as treasurer for the North Carolina State Association of Letter Carriers for the past 22 years.

But that’s about the change.

With his 74th birthday now on the horizon, he figures it’s time he handed over his calculator to someone else. While most, if not all, of our current state officers will be seeking re-election at this year’s state convention, Straub has made it clear that he will not.

“It’s time for a younger person to start doing it,” says Straub. “I didn’t want something to happen to me and everything be in chaos.”

When Straub first migrated from his home in Middlesex, New Jersey back in the late ‘50s, he never dreamed he’d be performing that service later in life. He hadn’t even dreamed of being a letter carrier. What initially drew him to North Carolina was a course in radio-tv-and motion pictures at UNC-Chapel Hill. Eventually, he realized he wasn’t cut out for that and dropped out of college in 1961, taking a part-time job. That job was so exciting he has since forgotten what it was.

But there was a job he enjoyed. During his summer breaks from UNC he had gone back home to New Jersey and carried mail.

So in the fall of ‘61 he approached Chapel Hill’s postmaster and asked him if he had any openings. He did, and a couple of weeks later young Straub was working as a clerk-carrier making all of $1.09 an hour, which was good money back in those days.

“I opened up parcel post in the mornings at 3:30,” recalls Straub, “ and worked until 6. If a route was open they’d put me on that route and I’d carry that until 2:30 or 3. Then I’d come back in and work dispatch or parcel post. A lot of these carriers now, they don’t realize what we went through. I’d work 75 to 100 hours a week, straight time. Back then there was no overtime.”

When asked what was a lesson he had learned early on he says, “They had an auxiliary route and were trying to get it made regular. I didn’t know any better back then, I was a greenhorn. I ran the route in about six-and-a-half hours. An old timer pulled me aside and in a stern voice he says, ‘Look, we’re trying to get this route made regular, we don’t need you running it in less than eight hours.’ So I learned my lesson that you don’t run a route.”

Although working 75 to 100 hours a week doesn’t give a young carrier much opportunity for dating, he somehow found the time. A co-worker of his, Rudy Tempesta, introduced him to a young woman who was working in his wife’s beauty salon.

“I had dated various girls and I didn’t find any interest in them,” says Straub. “But Carolyn was different. She was friendlier and was interested in our doing things together. And,” he adds, “we’re both Carolina fans, so that helped.”

The couple began dating in February of 1966 and were married in August of that same year. Come this August, they will have been happily married for 49 years. They have one daughter and a 16-year-old granddaughter.

By the late ‘60s Straub had become active on the state level, and was already serving as Assistant Secretary-Treasurer under the masterful tutelage of W.D. Haralson, who was for years the State Association’s Secretary-Treasurer.

“I learned a lot from W.D.,” says Straub. “He was my mentor as far as the state goes. He was one of the best persons I’ve ever met.”

At the time there was another young up-and-comer by the name of Wayne White. White and Straub became good friends. In 1968 Straub helped White get elected as president of the State Association. Nearly a decade later, he would once again help his friend win election as Region 9’s national business agent.

Says White of Straub, “He and I have been friends for 50 years through the union and we’ve been through a lot. I’ve found him to be a loyal friend, not just one who’s a fair-weather or good-time friend. He’s been loyal through thick and then. When I was business agent, he was a facilitator for me. I felt like I could trust him in any given situation.”

In 1974 Straub himself was elected the State Association’s president, with the help of White. In ‘76 he decided not to seek re-election so he would have more time to help White win his election for NBA.

One of those “thin” times White referred to was in 1977. That was the year Straub was diagnosed with cancer. In the short span of three months he went from 175 to 110 pounds. Thin times, indeed. But the chemotherapy was successful and today he is cancer-free.

In 1993 the position of Secretary-Treasurer was split, creating two positions in the State Association. Johnny Holland was elected Secretary and Straub, Treasurer. It is a position he has held ever since.

It may be a testimony to the outstanding job he’s done over the last two decades, or it may be that no one wants the job, or a combination of both, but only one person has challenged him in that time. And that one time wasn’t taken seriously.

David Summers was president of the State Association when Straub was Assistant-Secretary Treasurer. It was Summers who gave him the nickname “Squeaky.”

“If you happened to make a mistake in the arithmetic, “recalls Summers, “Danny would catch it. He had a red pencil and he would mark through it and put the proper amount out there so he would know exactly what to tell W.D. to write the checks for. When I had a problem, I always ran it by Danny.”

The current State Association president, Eddie Davidson has nothing but praise for his out-going treasurer. “What you want in a treasurer is someone who’s going to tell you when you can or can’t do something with the money. His whole purpose was to look after the money for the letter carriers and he’s done that. He’s the best I’ve ever seen at it.”

After 42 years of delivering mail, Straub retired in 2004, and was awarded Retiree of the Year in 2007.

His advice for today’s young letter carriers just starting out? “Go to branch meetings and get involved. If you don’t go to branch meetings, you don’t know what’s going on.”

He has already picked the person he wants to be his successor, Debbie Stone of Charlotte. “She knows all the mechanics of the job,” he says, “She knows what needs to be done.”

Asked what he will do with his free time now, he says, “There’s no free time when you’re retired.”

Branch 248's Maryann

Haire presenting Bob Mazzeo with his 45-year membership pin and

letter one week before his death on March

7.

Don’t Put Off Until Tomorrow What You Can Do Today

By Maryann Haire

Branch 248

Last July 2014 at the NALC Philadelphia Convention, I learned that National has membership service pins starting at 25 years and up at five-year increments. I’ve heard of gold pins at the 50-year membership, but these others I did not know. After consulting with our president, I set out to bring our membership up to par with these service pins.

We decided to award them during our 2015 Installation Dinner in January. Invitations went out and we had a large turnout for the dinner. The pins were awarded after the installation.

About two weeks later, I received a call from the daughter of 45-year member, Robert Mazzeo. She explained that Bob was unable to come to the dinner due to illness and asked if I would deliver the pin to him.

We agreed to meet at his bedside on Saturday, February 28. Bob was a past president of the Hendersonville NALC Branch prior to their merger with Asheville Branch 248.

At the end of February the single-lane mountainside gravel road which I live on was still icy and snowy. I called Bob’s daughter the morning of the 27th to be sure we were still on for the next day. Bob had just been released from the hospital the night before and was once again in palliative care.

I asked her if I should wait for the next weekend, but she said no. Bob had a very hard time and she wasn’t sure how much longer he would be around.

Saturday the 28th came and I headed to Hendersonville. Bob had his family by his bedside as I presented him with his 45-year service pin. I gave him special thanks from all our fellow and sister carriers for his hard work and dedication as a shop steward as well as president of his local branch.

Bob’s daughter pinned his 45-year pin on his collar. Bob beamed with joy and pride as I spoke to him. I talked with him about the difficulties of carrying mail full time plus holding an officer’s position in the branch.

Although Bob couldn’t speak during my visit, before I left he managed to push out a heartfelt ‘thank you’ when I shook his hand for the last time before I left.

On March 7, Bob passed, which was exactly one week to the day from our visit. If I had put this presentation off, Bob would never have received it.

So, as I was told so many times as I was growing up—and for the many times that it has been tested— “Don’t put off until tomorrow what you can do today!”

A Matter of Life, Death and

Eternity

The U.S. Postal Service’s first postmaster general, Benjamin Franklin, once wrote, “The only things certain in life are death and taxes.”

Hundreds of years before Franklin’s oft-quoted words, a man by the name of James wrote a letter to some area churches in which he made a similar statement about life: “For what is your life? It is even a vapour, that appeareth for a little time, and then vanisheth away.”

Yes, there are two certainties in life: We’ll pay taxes, and we’ll die. Both are inevitable.

We know what happens when we pay taxes, but what happens when we die? Since we’re all going to experience it eventually, wouldn’t it be a good idea to give it some serious consideration before it happens?

Several years ago the Barna Research Group found in one of their surveys that most Americans — 8 out of 10 — believe there’s life after death. And most also believe that everyone has a soul (although that may be hard to believe about some people), and that there is a heaven and a hell. Just one out of every 10 adults believe there’s nothing after this life. They believe that once you’re dead, you’re dead forever.

Said one respondent to an AARP Magazine survey on the subject of life after death, “Life’s short enough without having to worry about something you can’t do anything about anyway.”

Charles “Chuck” Hill, a Wilmington letter carrier, would take issue with those who believe that this life is all that there is.

Says Hill, the author of A Scriptural Guide To What Happens When We Die, “I cannot stress it enough that what you believe directly affects where you spend eternity.”

Echoing other books written on the subject, Hill believes there is more to life than the one we’re currently living and it would behoove all of us to do some research on the subject.

“I’ve heard people say,” says Hill, “’Well, how can you really know what happens when you die.’ My hope is that after reading this book, that question will be answered for you, or at least you will have a better understanding of life and death.”

Although this is Hill’s first published book, the veteran letter carrier began writing when he was 22 and had his early poems printed in his church’s newsletter. Those who recognized his early talent encouraged him to enter a poetry contest. The product of that entry was a poem entitled “The Church.”

Since then he has written widely, publishing columns in several papers over the intervening years.

A native of Canton, Ohio, Hill joined the U.S. Army after graduating from high school in 1977 and served with the 82nd Airborne Division. After his discharge, he worked on coal digging machines and then went on to make rubber floor mats for GM.

Not wanting to spend the rest of his life working in “a hot, dirty factory,” Hill applied for a job with the Postal Service and was eventually hired as a city carrier in 1987.

While still living in Ohio, Hill was a well known evangelist. In addition, he worked as an assistant pastor at one of the local churches and served as his branch’s chaplain.

When he and his family moved to North Carolina, he served as interim pastor at Silver Lake Baptist Church in Wilmington for nearly a year in 2002 and as senior pastor at The Community Church in Carolina Beach in 2005.

And so it was that for a number of years he delivered the mail on weekdays and sermons on Sunday. Although he’s not pastoring a church at the present time, he plans to return to the pulpit after he retires from the Postal Service.

When asked why his first published book focuses on the subject of death, Hill replies, “So many people have questions, or wrong ideas about death. (I wanted to) get the message out to open people’s eyes to what it takes to get to heaven.”

The 95-page book, which is published by Outskirts Press, is filled with numerous quotes from the Bible and commentary by the author.

In the introduction of his book Hill writes, “What you are about to read is truth. Truth sometimes hurts….You may be shocked or quite possibly offended at what the Bible says about certain subjects….I’m not trying to sway you to see things my way. I’m asking you to see it God’s way.”

His book, which was published last summer, has found wide appeal.

“I found out my book is going around the world,” says Hill. “A lady on my route bought one. She is affiliated with a group of English teachers located around the world. She sent it to one of them. When they get done with it, they send it to someone else. I believe she said it has been in seven countries. Each person who reads it, signs in the back with their name and the name of the country. Also, through the website, it is available anywhere in the world.”

Hill is now in the process of completing his second book, A Scriptural Guide to Prayer.

Hill’s current book, A Scriptural Guide To What Happens When We Die, is available from Barnes & Noble or as an e-book from www.outskirtspress.com/

Charles Hill

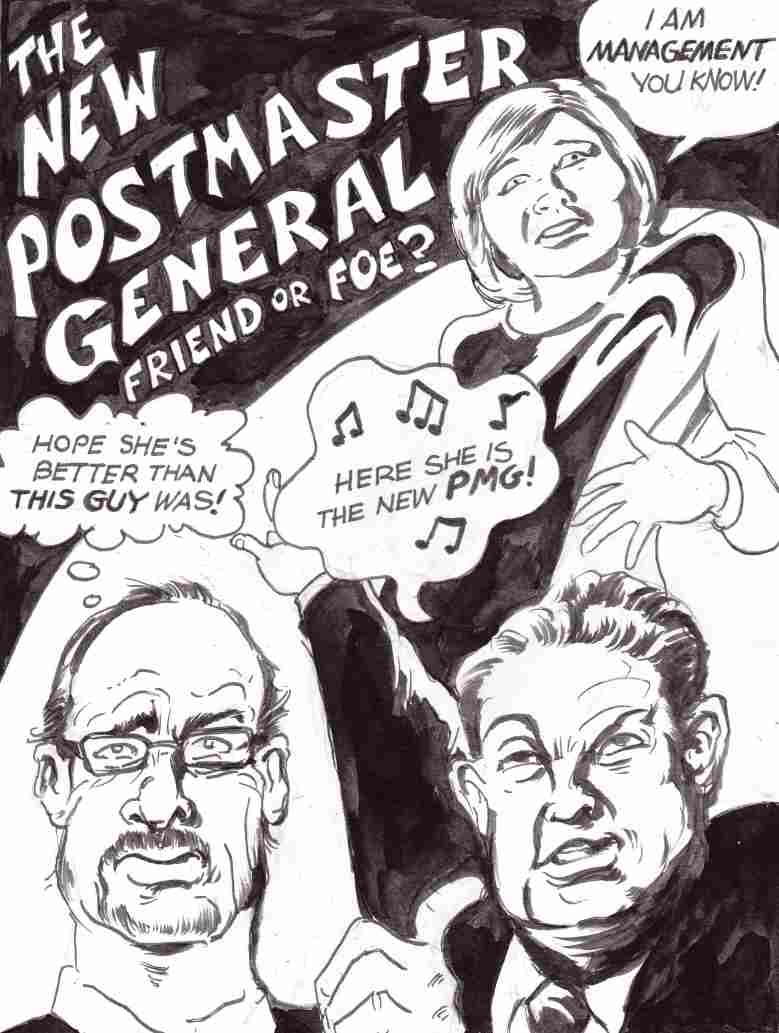

Art work by Fred Vance, , President, Branch

2794 Kannapolis, NC

A Faux Interview With

Outgoing Postmaster General

Patrick Donahoe

By Kevin Baker, President

NALC Branch 545

Charlotte, NC

NALC: Good day, Mr. Donahoe. Thank you for taking the time out of your busy schedule to meet with me. I am the NALC branch president in Charlotte, North Carolina.

PMG: The what?

NALC: The National Association of Letter Carriers.

PMG: Hmmmm. Sounds vaguely familiar. You know we don’t deliver letters anymore, right?

NALC: Um, we’ll get to that. Would you like to make any comments before we start the interview?

PMG: Sure! It’s been a great honor to represent the hard working men and women of my staff here at L’Enfant Plaza. If not for them I never could have begun the process of running the Post Office into the arms of private enterprise.

NALC: Anything else?

PMG:

No, that should do it.

NALC: OK, then, let’s begin. During your tenure you’ve seen mail volume drop significantly. Looking back, was there any way to avoid the drop?

PMG: The Internet took its toll on the mail volume, which was unforeseen. Any attempt by me to find alternative revenue streams would have been impossible. We just had to ride it out and downsize to meet the new lower demand.

NALC: Do you believe the NALC hand a hand in helping the Post Office remain viable?

PMG: Who?

NALC: Sir, we’ve been through this.

PMG: Oh, right, right. The NALC said they would enter into a joint route adjustment process, but really they just fought the process the whole way. The NALC didn’t want to cut the 30 percent of the routes that I projected weren’t needed. It was a waste of time and the taxpayer’s money.

NALC: You realize taxes don’t pay our salaries, right?

PMG: Sure they do. Where else would the money come from?

NALC: I can’t believe I have to explain this to you. Money from postal revenue, like postage, pays employees.

PMG: If that’s true, how do we pre-fund the health benefits for the greedy employees into the 22nd century?

NALC: Sir, I’ll ask the questions. But since you brought it up, why are we pre-funding the health benefits so far into the future?

PMG: I don’t know, but that Issa character won’t shut up about it. I’ll be glad when he leaves.

NALC: Well, that’s something we can agree on. Do you feel that private enterprise would do a better job of delivering the mail six days a week than the quasi-government system we currently have?

PMG: Absolutely. First, six-day delivery is just not financially feasible. A private company would see that you could do the same amount of business much more efficiently five or maybe four days a week.

NALC: But that would cause…

PMG: I’m not finished. Second, once you have four day delivery the unions would be busted and private contractors could be used for the actual delivery. That would be much cheaper for everyone!

NALC: Are you finished now?

PMG: I think so.

NALC: Wouldn’t reducing delivery days cause the demand for any delivery to dry up? Doing the same amount of delivery business wouldn’t matter because the business would go into steep decline.

PMG: That’s right. Then you could reduce the amount of delivery days even further if you wanted to.

NALC: But in short order, using your scenario, there wouldn’t be a Post Office to deliver anything.

PMG: That’s why I’m retiring, before that happens. I’m gonna get mine, understand?

NALC: I understand. Actually, many of your past decisions are making more sense to me now. How do you feel knowing thousands of postal employees would be left unemployed if your plans were to go into effect?

PMG: I can’t be responsible for other people not planning ahead and getting a golden parachute for retirement like I did.

NALC: That’s a very cynical way of viewing it. Do you take any responsibility for the recent ‘cyber intrusion,’ as you call it?

PMG: Well, you know, that was a very unfortunate thing that happened. It didn’t happen only to the employees, it happened to me as well.

NALC: That’s true, but you knew about it months before you made it

public. Don’t you think the people working under your direction

deserved to know as soon as possible, in case there was something

to be done?

PMG:

What could they have done that I wasn’t already doing?

NALC:

Information security plans are available. They could have had those

in place earlier.

PMG: Whatever.

NALC: This is the end of the interview. Do you have any advice for your replacement, Megan Brennan?

PMG: Yeah. Good luck. You’re gonna need it.

(Editor’s note: Both Kevin Baker and former Postmaster General Patrick Donahoe are real. This interview wasn’t.)

After 68 Years, America's Senior Letter Carrier Hangs Up His Satchel

After 68 years of delivering mail, Rudy Tempesta had experienced more than his share of hot, humid days. But today was different. Midway through his route along Summerset in Chapel Hill, NC, a route he had carried for over two decades, the extreme heat was taking its toll on his 89-year old body. Soaked in sweat and feeling ill, he decided to return to the Chapel Hill Public Library.

He had just staggered to a bench inside the library’s doors and sat down when he began throwing up.

The rest of the day became a blur: the people’s faces gathering around him, voices, the ambulance ride to UNC Hospital, more blurred faces and jumbled voices in the E.R.

Ironically, just a few days before this his postmaster had approached him out on the route as he was reloading his vehicle.

“Don’t you know you’re not supposed to drive without a seatbelt?” she had asked of the man who had driven a postal vehicle accident-free for more years than there were candles on her last birthday cake.

“I was wearing my seatbelt,” replied Rudy. “I unhooked it as I came to a stop.”

From there the conversation turned to the summer heat. As Rudy recalls it, the postmaster didn’t seem to think it was hot inside his truck.

“What?” exclaimed Rudy. “It’s 95 degrees in that damned truck. You’re riding around in an air-conditioned limousine and you tell me it’s not hot in the truck!”

Although this may be a typical conversation between a carrier and a supervisor or postmaster concerning what’s hot and what’s not on any given summer day, it was not typical for this postmaster and Rudy. Normally, the working relationship was respectful. But on this particular day, for whatever reason, the sparks flew.

Then, a few days later, Rudy finds himself in the hospital suffering from heatstroke.

Although Rudy could have died that day—much younger letter carriers have succumbed to the heat in the past—his life did not pass before his eyes. But if it had, these are some of the scenes he might have revisited:

The flashbacks would likely have gone back to 1925 and his birth in Brooklyn, NY to his two Italian immigrant parents. He would have recalled his happy childhood there and his four siblings.

The flickering video of memories long past would then have segued into his early adulthood and the two years he spent as a ball turret gunner hanging precariously from the bottom of a B-24 Liberator bomber in World War II as it flew missions over Nazi-occupied Europe.

It was during these two years that the teenager became a man and became acquainted with the specter of death as he and his fellow crew members flew through enemy machine-gun fire and maneuvered flack-darkened skies.

After his discharge he would recall his brief stint working in a machine shop and then the beginning of what would become a very long career with the postal service.

Harry Truman was president was president that year, the man who had famously said of his job, “The buck stops here.”

But when Rudy began delivering mail, the hourly wage was less than a buck. It was 85 cents.

Other scenes that would have skipped along the neural pathways of his 89-year old brain that day in September would have been the 12 years he had spent delivering mail on four floors of the Empire State Building, walking down long corridors that seemed like they were a mile long.

There would be memories of his first marriage and the birth of his first two children, Rudy, Jr. and Toni. He would have recalled his move from New York to Chapel Hill in 1959 and his early years as the city’s carrier and the branch’s president.

When he began delivering mail there they only had five city routes, and the UNC Hospital was just a brick building.

Shortly after his arrival Rudy’s coworkers appointed him as their new president. “Damn Yankee,” they laughed, “let him fight with the managers.”

And fight he did.

Even though his body was just on the outskirts of death that day in September, his mind would have recalled with a deep sense of satisfaction, the battles he had waged and won on behalf of his fellow carriers, carriers who had lost their jobs and then been reinstated with full back pay, all because of that “damned Yankee.”

“I like to fight for people,” he has told this and other writers over the years. “I enjoy winning arguments (with management).”

Had his life flashed before his eyes on that September 2nd, he would have recalled his second failed marriage and the birth of his three children, Erica, Nick and Alex. His recollections of the joy he felt attending their sporting events and his cheering them on to victory would have exploded like fireworks within his mind.

“Your family and you should always be one,” he has said. “When you’re gone, they carry on.”

Of course there would be the memories of the friendships he had made over the decades with both co-workers and customers alike. They were members of his extended family.

Undoubtedly, he would recall that other brush with death he had had, this one in 1996. Unable to move, he had been rushed to the hospital where he was diagnosed with toxic shock syndrome, a potentially fatal illness. His prognosis was so dire that the doctors nearly took him off life support. And had it not been for his eldest daughter, Toni, they would have.

******

An email from a coworker of Rudy’s, Diane Parrish, alerted me to Rudy’s condition and his plan to retire.

I knew if Rudy was retiring, it had to be serious. He wouldn’t be hanging up his satchel otherwise.

My wife and I visited with Rudy in his basement apartment in October. Rudy is sitting on his couch, his walker in front of him. The week-long stay in the hospital has caused the muscles in his legs to atrophy. “I can’t get around without it,” he says.

When I had interviewed Rudy a few years ago he had weighed 138 pounds. In the wake of his illness, he looks thinner, his hair is grayer. But he’s still as feisty as ever.

He tells me the problems he’s having with Worker’s Comp. He shows me a letter dated September 26. It reads in part: “When your claim was received it appeared to be a minor injury that resulted in minimal or no lost time. Based on these criteria and because your employing agency did not controvert Continuation of Pay (COP) or challenge the case, payment of a limited amount of medical expenses was administratively approved.”

He’s understandably frustrated. His family physician will resubmit the claim. (In mid-November he still hasn’t heard back from them. Fortunately, he has plenty of sick leave.)

“Someone wrote them (Workers’ Comp) a letter telling them I wasn’t out during my illness,” he says. “Why would anybody do that?” Why, indeed.

He’s also facing hurdles in getting his retirement processed. Lots and lots of paperwork to be filled out and filed. (In a subsequent conversation over the phone we learn that Rudy’s paperwork has been completed and he’ll be retiring on November 26.)

On the brighter side of things, Rudy says he’s received numerous phone calls, cards and letters, and visits from co-workers and customers. A co-worker will be coming by tomorrow to take him to the doctor.

During our conversation, the maintenance man stops by to see how he’s doing. Then his letter carrier, Newman, looks in on him and delivers a letter from a former customer who now teaches in Spain. The writer is Julia Daugherty, a young lady whose picture hangs on his apartment wall and who has become like a daughter to him.

“She’s a sweet kid,” he says. “You get close to them.”

Evidently there’s a certain closeness he has with his co-workers as well. Back in September a petition with 26 signatures was sent to President Obama asking that he send Rudy a letter of appreciation for his many years of service.

I have one last question for America’s senior letter carrier before I leave.

“Now that you’re finally retiring after all these years, Rudy, how do you want to be

remembered?”

“I’d like to be remembered,” he says, “as a good guy and that I cared about people.”

That shouldn’t be a problem at all.

Enjoy your retirement.

Rudy Tempesta outside his apartment in Chapel Hill, NC

Rudy and the crew of the B-24 Liberator bomber, "The Flying Coffin." Rudy is the 5th member from the left, front row.

Model of the B-24 bomber Rudy flew in as a ball turret gunner (bottom of the plane.)

Rudy gives a farewell salute to his fellow carriers.

Michelle Pastern: A Letter Carrier

Hero

When you’re a letter carrier, you never know when an ordinary day will suddenly turn into an extraordinary one.

For Michelle Pastern, seven months on the job as a CCA at the High Point post office, October 23 was an ordinary day until she stopped to deliver mail at the Red Dot Grocery.

“While I was opening the door,” recalls the blond, Long Island, NY, transplant, “I heard a man scream for someone to call 911.”

As she quickly took in the scene in front of her, she saw that the cashier was already on the phone calling 911 and on the floor was a man who looked at first to be having a seizure. Kneeling beside him was the man’s friend, the man whom she had heard yell out as she entered the store.

“I knelt on the floor and was trying to talk to the man to see what was going on,” says Pastern as she attempted the assess the seriousness of the situation.

“He was already on his side, so I turned him over a little bit more because at first I thought he was having a seizure because he was trying to talk.”

A former nurses assistant, Pastern realized then that this wasn’t a seizure, it was a heart attack.

The store’s cashier shouted over to the man’s friend and to Pastern that the 911 operator had told them to start CPR immediately.

The stricken man’s friend, desperate to revive him, began chest compressions but Pastern saw immediately that he was doing it wrong; he was compressing too far up for the compressions to be effective.

A certified CPR instructor, Pastern took over and began the compressions.

“I just did the chest compressions,” she says. “That’s all you really need. The American Heart Association has found that the compressions are just as good and effective as the breaths.”

She continued to do this until EMS arrived, six to 10 minutes later. A short time span but one that seemed, at the time, to last forever.

When the EMS workers arrived they immediately began full-fledged CPR.

Uncertain at the time whether the man was going to live, a distraught Pastern walked outside the store where she admits, “I cried like a baby.”

“It’s really intense when that happens,” explains Pastern. “I didn’t want to be in there breaking down in front of people. I waited outside for a little while trying to get myself together.”

Finally, one of the EMS workers came outside and told her the man had been successfully resuscitated. He was alive.

Relieved, but still shaken, she returned to her route.

When asked later if she, as a certified CPR instructor, had ever had to perform CPR in an emergency situation like that before, she says, “I had seen others do it. I’ve watched nurses and I’ve assisted nurses but I had never had to do it on my own, in that kind of situation. To walk in and go through that yourself, it’s intense, it’s really an adrenalin rush. My fear was that he wasn’t going to live, so that’s where my emotions came in because I didn’t know.”

Here’s something else she didn’t know. Her coworkers at the High Point post office had gotten wind of her heroics and planned a surprise party for her at the office a couple of days later.

That morning her supervisor called her and asked her to report earlier than scheduled. When Pastern walked onto the workroom floor later that morning she was shocked and noticeably overcome by emotion by what she saw. Her case had been decorated with balloons and colored ribbons. At the morning’s stand up talk in her honor, she was presented with a Certificate of Appreciation and a bouquet of flowers.

As for the importance of knowing how to perform CPR, Pastern says, “I told Dee (the postmaster), that I wouldn’t have a problem doing instructions over there. It’s a great thing to have. You never know when you’re going to need it.”

Although she hasn’t met the man whose life she saved, she has heard that he is home now and is greatly appreciative of the fact that she was there for him when he needed her.

Says Pastern, reflecting on the serendipity of that moment with a sense of awe in her voice, “If I didn’t have mail for them that day, I never would have been there. There was some reason that I was supposed to be there.”

And that reason was to save a man’s life.

Doing It For The Children

Apparently Jerry Smitherman has never met a charity he didn’t like. Although he retired as a Charlotte letter carrier in 2007, today, at age 70, Smitherman is more involved in community projects than ever before and is still going strong. By his own estimate there are anywhere from 12 to 15 charities that he is currently involved in.

He does it for Jerry’s kids. No, not Jerry Lewis, Jerry Smitherman and his kids.

“I’m a sucker when it comes to children,” admits Smitherman. “Anything for a child, that’s me. That’s what got me involved. And that’s what got me involved in a lot of this stuff.”

One of his oldest projects for kids is Toys for Tots. He’s now been involved in that for over 45 years.

“I fully believe in it,” he says. “It’s extremely rewarding.”

The same thing could be said of his marriage as well, which has also lasted for over 45 years. And no doubt his two grown sons and his grandchildren have helped to spur an interest in helping children.

While most men his age are beginning to slow down, Smitherman is still going full bore with his volunteer work encompassing food pantries, the USO at Charlotte Airport, What’s In Your Sand Box, Armed Forces YMCA, Schools Tools, and The Native American Heritage Association, just to name a few.

But for the purpose of this article we’re going to focus on his successful tenure as Branch 545’s Food Drive coordinator in the late 90s and up to his retirement in 2007.

Implementer-In-Chief

Normally you wouldn’t consider an On-the-job injury as something good. And although it wasn’t good for Smitherman, a diagnosis of tendonitis and carpal tunnel, plus a botched operation by a Charlotte surgeon, turned out to be a blessing for the thousands of the Queen City’s residents who turn to area food banks for food during hard times.

At first Smitherman considered his life of limited duty at the post office to be a “limbo.” But in due time he would turn that limbo into lemonade.

As the next Food Drive appeared on the horizon, Smitherman realized that his limited duty status freed him up to spend more time on preparing for it. Says Smitherman, “When I took over as food drive coordinator, I had the time to do it. I started from scratch, but I had all these ideas we discussed and I just implemented them.”

Smitherman wasn’t the main idea guy, but he was the one who would take other’s ideas and make them a reality.

During the nearly 10 years that Smitherman served as Charlotte’s food drive coordinator, there were approximately 30 station co-ordinators. These were not only from Mecklenburg county, but other surrounding cities and counties as well.

“We would have a meeting once a week, a month-and-a-half before the food drive,” recalls Smitherman.

The meetings generated a lot of good ideas including providing the customers with bags for the food, T-shirts paid for by sponsors, radio and TV advertising and

promotions, a kick-off in downtown Charlotte with the mayor as keynote speaker, banners, and even billboards.

The local Wendy’s sponsored the billboards for a few years, then Adams Outdoor donated five for the campaign.

In the beginning, Winn Dixie furnished paper bags that were delivered inside the Charlotte Observer. But since not all customers received the paper, Harris Teeter furnished bags that were delivered by the carriers, much like the postcards reminding customers of the second Saturday in May food drive.

In need of a phone when he took over as the coordinator for the food drive, Smitherman called AT&T Wireless and they gave him one.

Emboldened by that success, he then talked to the sales manager and asked if the company would be willing to advertise on the backs of 1,500 food drive T-shirts. He agreed.

Although Smitherman proved to be quite successful in getting sponsors for the food drive each year, there once was a time when he had his doubts.

“When I first started as coordinator with the food drive,” explains Smitherman, “I was going to these different companies and they were saying,’No, no, no.’ And I was disgusted. I’d go back to the car and I’d say, ’They’ve got the money, why won’t they help me?’ Then, one day I hit Bingo.

Bingo!

“Bingo! I finally realized, hey, not everybody’s going to help me. So, if I get a no I say, ’Thank you, I appreciate it,’ and I clear it from my mind. So that’s how it started upward; it was just a change in attitude.”

And that Bingo moment and the change in attitude resulted in his having a 90 percent success ratio in getting donations.

The day of the food drive, all the station coordinators saw to it that their carriers had a hot meal at lunch time.

“We’d have the carriers come back around 12 noon and unload their vehicles. Depending on the station, they’d have hot dogs, hamburgers, pizzas, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Honey Baked Ham and such. Pepsi Cola furnished the drinks.”

Food drive days were especially long for Smitherman who might not get home until midnight or sometime thereafter. He would stay up to get the totals from the various Charlotte stations before calling it a day. When asked approximately how many hours he would spend on each food drive he laughs and says, “A multitude.”

The first food drive under Smitherman’s leadership was a smashing success, shattering Charlotte’s old record by double the previous amount. He’s quick to point out, however, that the only reason the food drive has been such an overwhelming success over the years is because he, unlike his predecessors, had the time to invest in it.

And because of the dedication of the station coordinators, and management, Charlotte has consistently set the standard by which all other branches are judged.

Not everyone who is a letter carrier, carries the mail.

There are those carriers who begin their careers by carrying the mail and then, somewhere along the way they become something else, someone who aids those who carry the mail. As such they are required to wear many hats: they are mentors, sages, teachers, life coaches, experts on the National Agreement, advisors, conflict resolution specialists, piñatas, defense attorneys, shoulders-to-cry-on, and confidantes, just to mention a few. Within the Postal Service and the NALC you will find them in every state and in every region of the country.

Paul Barner of Georgia is one of these people. Although he is still has a fulltime carrier assignment in Roswell, Georgia, since February of this year he has been working as a Regional Administrative Assistant for Region 9 out of the National Business Agent’s office in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

One could say that his life’s journey from Bainbridge, Georgia, to his present position as a NALC RAA, has been rather serendipitous.

Like many teenagers, Barner wasn’t sure what kind of career he wanted to pursue when he graduated from a Seneca, South Carolina high school. Job opportunities then, as they are today, were scarce.

He decided to join the Army and sort things out there. He landed a job in Army Intelligence where he became a electronic warfare Morse intercept operator.

“I thought it would be an interesting field to get into, something a little bit out of the ordinary,” he says. “I had top secret clearance with quite a few extra caveats on it that boosted it up quite a bit.”

He served for four years, and then an additional two as a Reservist, but in the end still hadn’t decided on a career.

Upon his discharge Barner and his wife moved back to Georgia where he began attending college on the G.I. Bill, majoring in real estate with an emphasis on developing and building.

“I had a construction background,” says Barner, “so I began developing subdivisions. And I actually live in one of the subdivisions I developed. I still play with real estate some, not so much developing any more but buying, selling, speculating, doing some minor flips of houses.”

But the real estate work wasn’t scratching his itch. Besides, it was the late 80’s, the economy had tanked and the real estate market was in a slump. He needed something that would provide more financial security for his family.

He had taken the postal exam soon after his discharge from the Army. Then, in 1987, the Roswell, Georgia post office called asking if he was still interested. He was.

“I had a subdivision on the ground and luckily I had paid off my construction costs,” recalls Barner. “So I went to work for the post office so I would have a steady income and would be able to provide for my family without having to dump those lots.”

It would take two years before Barner decided he had finally found his career niche.

“I enjoyed it,” says Barner, and you tell by the expression on his face that he really did. “And I decided, ‘Hey, this is a better life than the construction business.”

But this is not to say that working conditions were perfect. Becoming dissatisfied with the way some things were being done, he joined the union, ran for a shop steward position shortly thereafter and set about correcting the problems.

He would remain a steward until 2008.

Barner says of his years as a shop steward, “You don’t just represent the employee, you are a sounding board for them. It’s more than just a contract thing; they rely on you for basically everything. You have to be a jack-of-all-trades. I’ve even bailed a member out of jail at 3 o’clock in the morning,” he laughs.

Barner is quick to credit his branch president, Bob Johnson, for mentoring him and for paving the way for his next union role, that of arbitration advocate. In addition to being the branch’s president he was also an arbitration advocate. Barner adds that Johnson is still branch president today and has been with the Postal Service now for 46 years.

Of his role as a letter carrier advocate, Barner says, “That’s where the rubber meets the road. As an advocate there is no further appeal, that’s where the final decision is going to be made. It’s high pressure, but very interesting and rewarding. And it’s fun, too,” he says with a smile. “I’ve done cases in Miami, Florida, and in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. I’ve done cases from one end of the region to the other, and everything in between all four states of the region.”

You would think someone with that kind of responsibility would be a Type A personality, but not Barner. He’s laid back and cheerful.

In 2008 he was appointed as a Step B representative.

Barner says he’s never really set his sights on any particular job within the union. He just does the best he can at whatever job he has and everything else just seems to flow from that.

In spite of his work as a Step B representative and letter carrier advocate, he never dreamed of ever becoming an RAA.

“I’ve always told the people higher than me, whatever role they feel like I’m best suited for, that’s where I’ll go,” he explains. “Wherever they think I’ll be the most benefit to the membership and the union, that’s where I’m willing to go.”

Being a RAA is definitely not a job for the faint-of-heart. A typical work day at the National Business Agent’s office begins at 8 a.m. and may not end until 8 p.m. The job can also eat up one’s weekends.

And of course there’s the travel. RAAs spend a lot of time either on the road or in the air traveling to their next destination.

“I enjoy the work,” he says, “I find it very interesting. I love the union and the people associated with it. The enjoyment and pleasure, the fulfillment you get from it, to me, outweighs the sacrifice.”

He adds that his two mentors, branch president Bob Johnson and former RAA Chuck Windham had told him early on that the work could get into his blood. They knew from experience.

You don’t have to talk with Barner very long before you realize it’s definitely in his blood.

When asked about any goals he has set for himself as the newest addition to Judy Willoughby’s team, he says, “I guess my goal is to provide the best training, the best information I can to the branches and the membership to help them have a more productive and satisfying career. I’ve always been one to go to work with a smile on my face and to leave the same way. I think every employee should be treated in a way and have a job where they can do that also. We spend the majority of our lives at work. My goals are to do everything I can to make that happen.”

Caps for Kids

If you think bottle caps are only good for keeping the contents of a container from spilling out, you’re wrong.

The cap on that water bottle or that soda bottle you just tossed in the trash, could have helped to save a child’s life.

Up until three year’s ago members of Branch 3984 in Jacksonville, NC were tossing their caps away, too.

But not any more.

Letter carrier Lee Raines’ wife, a teacher’s aide at a Jacksonville school, heard an extraordinary story at school about a local doctor who was treating kids with cancer for the cost of a bottle cap. For every 1,000 bottle caps—any kind of bottle caps—he would see to it that a child received a free treatment of chemotherapy.

Cap-tivated by his wife’s story, Raines took the information to his monthly branch meeting.

The response from the membership was overwhelmingly unanimous: Let’s do it! Let’s collect bottle caps for the kids.

Since Raines had brought the news to the branch, he volunteered to get the ball (or caps) rolling by heading up the “Caps For Kids” project.

The letter carriers quickly got the word out to their stations and customers and the caps started rolling in—thousands upon thousands of caps, enough to fill up the back of Raines’ pickup each month.

Observes branch member and Area Three representative Bob Wahoff with a smile, “I don’t think he (the doctor) really understood how many bottle caps a bunch of letter carriers can collect.”

Wahoff, along with fellow carrier Tom German and a rural carrier, now co-chair the project.

Due to confidentiality laws the carriers don’t know the identity of the doctor or the children that are being treated. Nor do they know how caps are converted into currency. All they know is that the children being treated are elementary children under the fifth grade.

Says Wahoff of his route: “I have about fifteen businesses that give me caps, all the time. I’ll go to a customer and there’s a box of bottle caps. I’ll go to a customer’s mailbox and the flag will be up and I’ll open the box and it’s full of bottle caps.”

And the cap collecting isn’t just confined to Jacksonville.

“A man in a business talked to his sister in Havelock. She talked to the hospital and they collect bottle caps and send them to him and he gives them to me. A lady’s sister mailed her a box of caps from New Jersey. We’ve even heard that Marines are flying bottle caps from Japan to Cherry Point and then deliver them to the fire department on Marine Corps aircraft.”

It’s to be noted that a hoax spread across the United States in 2008 claiming that caps could be collected for chemotherapy treatments resulted in thousands of caps being collected by schools, churches, civic groups and other organizations before it was discovered the campaign was a scam.

In that particular case there was never a designated distribution point for the caps. In other words, there was never a way to actually get the collected caps to the unidentified doctor or hospital. In Jacksonville, however, there is a distribution point to receive the bottle caps and see to it that the unidentified benefactor receives them.

“The doctor spoke to the Rhodes Town Fire Department,” says Wahoff. “The fire department is heading it up. We collect the caps and deliver them to the fire department. They get them to the doctor. We’re nothing more than a collection agent.”

Although the branch isn’t collecting as many caps as they did when the campaign first began three years ago, they still take in close to a thousand caps a month, enough to provide some child with a free chemo treatment.

“So far,” says Wahoff, “we have two children in remission and we have two children being treated. These are children who got a bad hand and we’re trying to make it a little better for them.”

Those who would like to collect and then send their caps in may mail them to Bob Wahoff at 920 Eton Drive, Jacksonville, NC 28546. Or for those planning on attending the State Association’s fall training in Clemmons, NC this October, bring them with you.

Says Wahoff: “It’s such an easy thing—bottle caps. We throw them in the garbage. These caps are life to somebody.”

Kevin Baker Graduates From 11th Leadership Academy

By Richard Thayer,

Editor

“I’m retired from the Army, so I’ve been to a lot of leadership training and this was easily the most effective training I’ve been to.”

The speaker is Kevin Baker, vice president of Branch 545 Charlotte and North Carolina’s most recent graduate of the NALC’s Leadership Academy.

Baker, a letter carrier since 1997, was one of 30 carriers who attended the 11th Leadership Academy (Winter/Spring 2011) with week-long sessions in January, March and May of 2011.

Among the various classes offered at the Academy are those taught on the National Agreement, the Dispute Resolution Process, branch financial responsibilities, DOIS, effective negotiation techniques, legislative training, public speaking and much more.

“They give you information then they break you out into groups and have you work in smaller groups to develop answers to different problems they give you,” says Baker of the intensive training that is conducted at the National Labor College in Silver Spring, MD, just a few miles north of the nation’s capital.

“What I thought was going to be my least favorite class turned out being my favorite,” he says, “public speaking. They really put you through the paces and by the time you’re done it’s no longer a weakness and you feel more comfortable."

Baker says that another enjoyable part of his Academy experience was interacting with the national officers who teach many of the courses.

“Probably half the courses taught are either by a present national officer or a past national officer,” he says. “They obviously know what they’re talking about and you understand what they’re doing for the union and how you fit into the grand scheme.”

Baker, who was born and raised in Nebraska, comes from a union family. His father was a member of the Sheet Metal Workers.

Knowing the importance of unions, he immediately joined the NALC soon after he was hired as a letter carrier in Charlotte, NC.

His first union office was that of alternate shop steward, a position he held for three or four years before moving up to shop steward.

Then a few years ago branch president John Walden asked him to

run for vice president. It was Walden who acted as Baker’s mentor

for the

Leadership Academy and who recommended him as a candidate to national headquarters.

“The Leadership Academy enabled me to see that we have a lot of talent in the union and a lot of it is not being tapped,” says Baker. “As I came back from the Academy I tried to express this to my branch. A lot of people just hadn’t been asked to get involved. We’ve been trying to do that now with good response.”

Baker adds that North Carolina has a lot of leadership potential and that he is hopeful that more carriers will be submitting their applications for the Leadership Academy in the future.

William “Bill” Wray of Branch 459 Raleigh is currently attending the NALC’s 13th Leadership Academy.

(Pictured: left to right, State President

Cliff Davidson, Jr., John Walden, National Business Agent Judy

Willoughby and NALC Assistant Secretary Treasurer Nicole

Rhine)

2012 Retiree of the Year John Walden Is Not Quite Totally

Retired

It’s still dark outside most mornings when John Walden, President of Branch 545 Charlotte, enters the branch office and prepares for another full day of work.